Article 1: An Interview with Elder Edwin Jebb, A Survivor of Canada’s Residential School System

Vritee Marrott

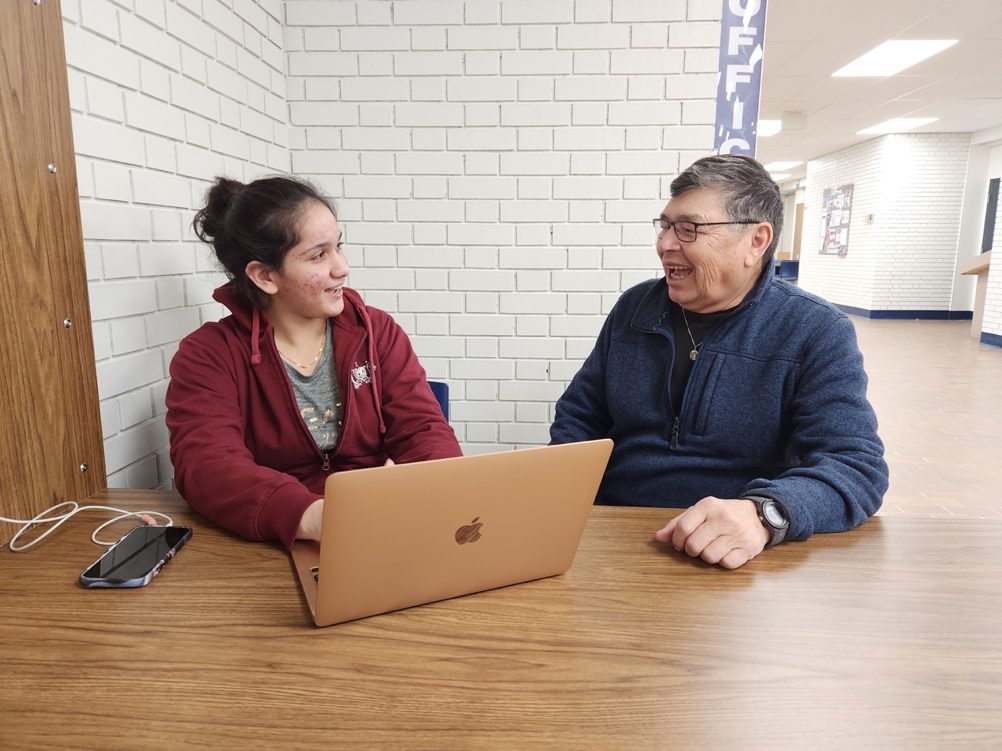

On a cold December 2nd evening, I was blessed with an extraordinary experience. I had the uncommon privilege of sitting down to a one-on-one interview with a survivor of Canada’s residential school system. This particular survivor is not just any person. He is also the chancellor of the University College of the North. Elder Edwin Jebb of the Opaskwayak Cree Nation (OCN) in Northern Manitoba is well beloved, and he is a crusader of education, Western and Indigenous. Despite Elder Jebb’s elevated status in the community and the Province of Manitoba, he is simply down to earth with an unrivaled sense of humour. To see a survivor of such an unholy experience, exhibit such warmth, affection, and understanding everywhere he went is truly inspiring. Such an attitude to life as shown by Elder Jebb inspired the realization in me that I should always strive to live above life’s adversities.

In this interview, I asked Elder Jebb questions ranging from his family background, his experience in the residential school, his take on Western education, and his view on truth and reconciliation, among other subjects of interest. I have decided to present this interview in a dialogue format so that the reader can easily follow the questions and responses without interspersing them with authorial or other impeding comments.

My name is Vritee Marrott, and I am inviting the reader to take this journey of discovery with me into the world of Elder Edwin Jebb, who is also the Chancellor of the University College of the North and a residential school survivor.

Vritee: OK, so I’m going to start with a general question, which is where did you grow up?

Elder Jebb: Where did I grow up? Here, here in the Opaskwayak Cree Nation. I was born in 1951.

Vritee: Can you tell me a little about your childhood, maybe your favorite memories?

Elder Jebb: Oh, my childhood memory would be being at home. That’s a good memory. Another childhood memory of mine was Christmas, which is a big celebration for us in North America. And just being home for Christmas was a good memory because I went to residential school when I turned 6 years old.

Vritee: What would you like to share today about your residential school experience?

Elder Jebb: Yeah, maybe I’ll go back and say that before I went to residential school, I lived with my parents. We had a large family, and both my parents went to residential school. My mother – 12 years – my dad maybe two or three or something or four years. He never talked about it. My mother talked about it a little bit. It impacted our lives, and it showed in their behavior. I could recognize that later in life, and it caused problems for all of us, you know, for our family, especially in my relationship with my father and my mother. My father was a trapper and a hunter. He spent a lot of time on a trapline and so I still do that. I go out there, and spend a lot of time in a trapline. When I went to residential school, I had just turned 6 years old. It was October, mid-October 1957.

I turned 6 in September; so, I was six years old when I got taken to residential school, and I spent nine years in residential school, which was institutional. It’s like a little jail, you know, where there’s no love and a lot of cruelty, a lot of abuse, all kinds of abuse – right from mental, physical, sexual, and spiritual. Everything. So, you come out cold, emotionless. But you can ask me what direct questions, yeah.

Vritee: Thank you for the encouragement. Do you have any memories of people, events, or experiences that stand out in your mind that you wish to share?

Elder Jebb: Yeah, the friends that I made. Children and grandchildren of people that went to residential school where we bonded like this [he demonstrates bonding by hooking up his two index fingers] because we were there together, you know, in this place of evil. We were there together. We bonded because we knew what we went through. They knew what I went through. So, we bonded. And it’s almost like when we got out of there, we never talked.

We never talked about it till it was okay to talk about it 30 years later. Now we can talk about it freely. But for years it was a secret, open secret with our families and our communities. When we didn’t talk about our experiences, we just left them unsaid. You could equate that to the experiences of people who went to war. They don’t talk about their trauma.

And the experiences that they had just sat with each other but not with the general public. Now it’s okay to talk about it – those that went to war and experienced trauma, and those who went to residential schools with their traumatic experiences.

Vritee: Can you tell me about your first day at a residential school?

Elder Jebb: No, I don’t remember. I got, I got taken by my mother and I got left there and that’s all I remember. Well, I was six years old young. However, one experience I had that I remember was a few months after I got there [residential school]. I was six years old. This little girl comes bouncing along. She was about four or five years old, a child, and she stops and kisses me on the cheek. I hated her because everybody laughed at me. She kissed me. But you know, children, they hug and they kiss. It was a spontaneous gesture on her behalf, just jumping along and just giving me a kiss on the cheek. She’s four or five years old. I told her that story, but she didn’t remember that. Of course, we don’t remember those kinds of things or many things. Just a few things.

Vritee: What was a typical day like at a residential school generally?

Elder Jebb: Lights, and you go wash up, get ready, go downstairs, after which you’re dressed and you go have breakfast. And then there’s a little break. Classes begin at 9:00 until maybe 12:00 o’clock, and it’d be lunch. And we go back to class at 1:00 till maybe 4:00 or whatever. And a little break and you go play outside. Later, it would be supper, and then after supper, you go play outside again. Bedtime soon followed, depending on the age you were. Younger boys go to bed at eight o’clock, while older boys go to bed at 9:00. I’m not sure what time everyone got up. I think it was 7:00 o’clock.

We learn those things that you need to survive out in the bush; how to make little shelters, and how to cook animals after hunting. I learned from the older boys, yes. We did all that playing and re-enacting what they do. So, we’re with nature and we’re out on the land. I think it really saved us. Yeah, in a lot of ways. I still go out on the land a lot.

Vritee: Is that the reason you enjoy spending a lot of time outside?

Elder Jebb: I think I’d die if I couldn’t. I have a cabin in the Bush, and I still go out there –almost every weekend or every second weekend in the summer, and I got a boat. In the winter I go by snow machine. I do a lot of fishing. I don’t commercial fish very much.

Vritee: Can you tell me about some of the tougher experiences that you had while at the residential school? Something you feel comfortable sharing.

Elder Jebb: Well, I wouldn’t really talk about the sex abuse, but it was rampant. I think I was about 12 years old. We had a supervisor that looked after the boys our age and he was a real sadist then. He liked hurting kids. I really thought it gave himself joy out of hurting kids. They called him Mr. Big Boy. We started calling him that one day in April. Our pants had got wet from melting snow while we were playing. He picked up a hockey stick, lined us up and struck our buttocks with the stick. Boom. Next, boom. Luckily for me, before he got to me, the stick had broken, and I think he got tired, or he got his anger out so he stopped hitting. Although he didn’t get to hit me, nevertheless, it was a terrifying experience. Yeah.

Another bad experience was how they ensured we did not speak our own language. During my earlier days at the residential school, we could speak Cree, our language. My first language is Cree. I didn’t know any English when I went to school. So, what they did was, they gave us 10 tokens. And on Friday, if you had less than five, you couldn’t go to a party that was being had. But later on, they just started hitting us if we spoke Cree. However, after a few weeks or a month, we learned not to speak Cree. We just spoke English as best as we could.

When I was in Grade 12, my father said to me: “You’re 17 years old, quit school and go to work. You’re a man now.” But I knew. I knew deep down that I wanted more. I wanted an education, and my mother didn’t encourage me to go to school either. But at the same time, my mother was brainwashed also. I’ll use that word.

When we talked about the bad stuff of a residential school, my mother would say, “don’t talk about it.” You know, like that was an okay place, but it wasn’t a good place. Some older people, my parents included, don’t go there [meaning they don’t like talking about their experience in rez schools]. They just start telling lies. But I didn’t listen. So, in a way, I love my parents. Maybe my dad, not so much. We clashed because I did what I wanted to do. I was a nice kid that never got in trouble, but I still didn’t take to their advice of not furthering my education. On this subject, I went against their will and their ideology which was influenced by how they were brought up. I went my way because I was already seeing that there is something better than this. I don’t have to be colonized. I should say. I don’t have to be.

I knew I could do more. I got an education, which is, you know for a lot of people, you’re not just fighting the system, you’re also fighting your parents just to be able to go to school. This is a difficult situation to find oneself in because my parents and their generation of survivors were working on the premise of the white man and his system. A little thing can trigger you because you’re always angry.

MFTN editor: That’s part of the thing we’re trying to do with muses from the north. Keep the conversation going.

Elder Jebb: Indeed! An important pathway to healing is dialogue. People must agree to talk. However, one of the things that’s really hurting though is the drugs that are being imported into our community. You know the meth and all that — the last 2-3 years had been really bad. In the city of Winnipeg for example, there are senseless, random killings. I have never been afraid to walk anywhere, not even in downtown Winnipeg. But these days, I am beginning to think that one needs to start looking over one’s shoulder.

Talking about healing, first we have to resist the temptation of hard drugs in our community and heal from past effects. I have a few friends that I’m working with and they’re sobering up. I admit that sometimes it is difficult working with people who have abused substances, but I am encouraged by the fact that everybody has a soft spot. And I know how to read people.

Vritee: Would you like to tell me what is one of your favorite memories from residential school?

Elder Jebb: Making friends, those friends that we had and we meet many years later. We bonded when we were in school so that’s the thing. We connected years later as well, so that’s the good experience – friendships that I had and developed through the years starting from our days at the residential school. As a matter of fact, I was closer to my friends than I was to my own family.

Vritee: Would that be because you stayed in school more than at home? How often did you go back home?

Elder Jebb: For us, and because we lived so close, we could go home on long weekends. But some of my friends only went home at Christmas and some of my other friends only went home in the summer. I have a few friends that didn’t go home for three years at least. And when they finally got home, they had grown so much that their parents had a hard time recognizing them.

Vritee: Is there anything that you would like Canadians to know about residential schools specifically?

Elder Jebb: Well, yeah, the truth. You know the truth that these things did happen because when we first started talking about it, a lot of people, including the Church, denied it. The Pope himself finally apologized last year. You know, I have people here in this community that I had a fight with because they denied it. That symbolizes how people are feeling. Now we are working to find a common ground where no one has any reason to doubt the unpleasant history.

Vritee: Do you think the best way to heal is through education or is there some other way that is more feasible?

Elder Jebb: I think education and the ability to have a good career and look after yourself, not to be dependent on the government or anybody else, is what will help us out. You can’t be angry all your life. It’ll keep you down. And physically, it’s not even healthy for the body as well, right? It is unhealthy for someone to be bottled up and angry within. Some say if you carry hate, you are like a person taking poison and expecting the other person to die. we cannot live like that; we cannot live in such a negative mindset. So how do we go about addressing the situation and changing things too?

Education and awareness about what happened. That’s why you have Memorials, walks, and dinners to talk about, and make people aware. It’s not just the white man but also our own people. They don’t know. They didn’t know our issue because we didn’t talk about it yet. We didn’t talk about what happened there. They hear a little bit now and then. And then a lot of time they don’t even know that they themselves are affected because their grandparents might have gone to residential school.

I was from age 6 to 14 in an institution. We didn’t know how to be parents because we grew up in a little jail, that’s what it was. We kind of made amends in our own way. When we were growing up, we were always clashing with our parents. I didn’t listen to my father. He told me to quit school. But you know, at the same time, he didn’t know how to show his love. But I know he loved me and same with my mother, but my mother never hugged me. I suppose the last time she hugged me was when I was an infant or up until I was 6, but not after. Now I have my own kids and I still hug them. we have to change. We have to change the way we do things, the way we show love. But the worst thing they did to us, among other things, is we didn’t know how to be parents. Imagine a family where all the kids are taken away. What happens to those parents that are left behind in the community? There are no kids playing, and when they come back they’re almost like strangers.

Their world changed with the scooping of their children. There’s nobody sitting there around that supper or breakfast table with the kids gone. So, you know we forgot about the parents. How it must have been to have your kids taken away? Yeah. And my parents didn’t try to hide us when the priest came and told my parents that we had to go. My parents were obedient and they said OK. They got us ready and we went there. They didn’t challenge the priest or their cohorts. Some parents challenged them, but our parents were obedient in that way because they thought that church was beyond reproach.

Vritee: We were talking about truth and reconciliation some time back, so, what do truth and reconciliation mean to you, as a survivor of the residential school system?

Elder Jebb: Reconciling differences, you know not just with the church, but with your own self and also people who might have hurt you and people you have hurt. Reconciling your differences with the establishment and the white man and learning how to live together. Right? For me that’s reconciliation. But they have to understand us. They have to know our history. Why what happened, happened, and that’s where the truth comes in. Truth is acknowledging what happened at those schools, while reconciliation is being able to live together, work together, and help one another.

Vritee Marrott’s Reflection on the Interview with Elder Edwin Jebb:

Elder Jebb’s welcoming nature helped me understand his story with great clarity. He explained the residential school system, the depth of intergenerational trauma, and its lasting effects on victims and survivors with the knowledge of captivating personal experiences. With the help of Dr. Joseph Atoyebi, one of the editors of Muses from The North, I was engaged and able to communicate with Elder Jebb effectively. Elder Jebb is very pleasant to talk with. We talked about truth and reconciliation, as well as charismatic small talks about football. Elder Jebb even told me about his Panjabi roommate while at the University of Manitoba. Overall, the interview gave me a pronounced firsthand exposure to a critical part of Canada’s history.

Author Bio:

Vritee Marrott recently completed her first year of Bachelor of Arts at University College of the North. She was born and raised in the urban city of Mumbai, India and moved to Canada to pursue university-level education in psychology.

Instructor’s Remarks:

I have had the privilege of instructing Vritee Marrott in her first year of university education at the University College of the North (UCN). Vritee showed in my ENG.1002 class in 2022/2023 academic, and her first essay in the course proved that she is a strong writer and student with outstanding potential. Vritee couldn’t have come to UCN at a better time, especially for MFTN, following the departure of our erstwhile student editor/print designer, Elizabeth Tritthart. Vritee is truly an asset we are fortunate to have on board. Her interview with Elder Edwin Jebb is genuinely inspiring. (Dr. Joseph Atoyebi)