Article 9: The Environmental Impact of Over-Harvesting in the Fur Trade

Kelly Laybolt

It has been universally accepted that the Canadian fur trade caused extreme environmental degradation as fur bearing animals were over-harvested to near extinction; however, there are many different opinions about the causation of this ecological damage. Traditionally, Indigenous people have been associated with the environmental wisdom worldview, and they are thought of as protectors of the environment. Despite this notion, previous research about Indigenous involvement in the fur trade has suggested they were responsible for the ecological degradation of fur bearing species because their primary role was the harvest and acquisition of furs. Throughout the 21st century, however, the truth and reconciliation movement between the Government of Canada and Indigenous people has prompted researchers to re-evaluate the involvement of Indigenous people in the history of Canada. According to the Government of Canada website, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) was established to “facilitate reconciliation among former students [of residential schools], their families, their communities and all Canadians”[i] The website further stated that the TRC published the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to Action in 2015, which consisted of ninety-four Calls to Action that highlighted Indigenous issues and Eurocentric processes that needed to be addressed or amended by the Canadian government.[ii] Several of the Calls to Action, including the 57th and 79th Calls to Actions, requisitioned the Canadian government to provide greater education about Indigenous culture in schools and include Indigenous involvement in the history of Canada in educational as well as historical institutions.[iii] University College of the North (UCN) has developed a curriculum that educates students about Indigenous culture, history and ongoing social issues that have continued to affect Indigenous people in an effort to promote truth and reconciliation within their campuses. With this focus on education about Indigenous history within the UCN curriculum, students have been able to gain an understanding of Indigenous involvement within the history of Canada and use this newfound knowledge within their works. As such, this paper argues that despite the postulation that Indigenous people were solely responsible for environmental degradation during the fur trade, it has been determined that ecological damage during the fur trade was the culmination of multiple factors including increased fur harvesting as a result of inflated pelt prices, increased reliance on European trade goods as well as an inadequate legal system to hold trappers accountable for abusing Indigenous sustainability efforts. Therefore, ecological degradation during the fur trade was a multi-faceted issue in which both European traders and Indigenous trappers were responsible for the aftereffect.

Indigenous people have maintained an environmental wisdom worldview as they worked closely with the land and sought to reduce their impact on the environment as much as possible. According to historian Arthur J. Ray, “there is little evidence to suggest that the Indians had seriously depleted the resources of the region in their efforts to obtain commodities to barter at the trading houses.”[iv] During the fur trade, beaver pelts were separated into two different categories: parchment beaver and coat beaver.[v] Parchment beaver consisted of pelts from beavers that were hunted strictly for the monetary value of their fur and coat beaver consisted of pelts that were used for clothing before being traded to the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC).[vi] Prior to increasing pressures for beaver pelts from the HBC, Indigenous people generally supplied the HBC with coat beaver because it was a more sustainable alternative to parchment beaver.[vii] Although the HBC began to encourage Indigenous trappers to bring parchment beaver for trade, Indigenous people maintained their sustainability efforts throughout the mid-1700’s and a majority of furs brought to trade were coat beaver.[viii] Therefore, Indigenous people continued to practice sustainable harvesting techniques as they strove to reduce their impact on the beaver population throughout the early to mid-1700’s.

Indigenous people also displayed environmental stability through their acquisition habits prior to being influenced by Europeans. Ray stated that “in the early years … [Indigenous people] did not engage in trade to accumulate personal material wealth for the purpose of gaining higher social status.”[ix] Indigenous social status was determined by displays of generosity which reduced the amount of trade goods Indigenous people desired.[x] Additionally, most Indigenous societies were nomadic, and they changed locations for a variety of reasons including seasonal weather changes as well as following animal migration patterns. Due to their nomadic lifestyles, Indigenous people only acquired goods “for their recognized utility” and did not accumulate any excess commodities”.[xi] As a result, Indigenous people only harvested enough beaver pelts to meet their essential needs which reduced the overall number of animals harvested for trade goods. Thus, throughout a majority of the early 18th century, Indigenous trappers maintained an environmental wisdom worldview by continuing to supply the HBC with coat beaver and only engaging in trade to acquire what they needed.

Environmental degradation began to occur as the fur trade industry became increasingly lucrative, and competition from French traders resulted in increased pelt prices. Ann Carlos and Frank Lewis stated that from the mid 1700’s onwards, an expanding French presence around York Factory and Fort Albany threatened the HBC’s monopoly in these areas.[xii] French traders proved to be fierce competitors because they employed different trading practices which made it more viable for Indigenous people to trade with the French instead of the English. According Carlos and Lewis, English traders “waited for the Indians to come to the Bay rather than actively going out in pursuit of furs.”[xiii] This method was inefficient because it created a “radial trading pattern” that left substantial gaps in the fur bearing territories the HBC claimed.[xiv] Carlos and Lewis continued with their explanation of this competitive fur trade business by explaining that in “contrast to the radial pattern of the English trade, the trade from the St. Lawrence was linear, with voyageurs continually pushing farther northwest and southwest in search of new sources of supply.”[xv] This linear approach provided Indigenous trappers with an easier trade option as French traders would travel to Indigenous communities to collect furs directly from the trappers. As a result, HBC’s revenues began to drop and they increased pelt prices in an effort to entice Indigenous people to resume trading with the English.[xvi] The economic change brought on by competition between European traders would prove to be disastrous for the beaver population.

European traders and Indigenous people capitalized on the favorable economic opportunity that resulted from European competition which decimated the beaver population. Economist John McManus indicated that prior to the fur trade, Indigenous people often forwent harvesting beaver because it was not a viable option to support Indigenous families due to the difficulties associated with harvesting these animals and the lack of resources that beaver provided. however, with the increasing demands from European traders, increased reliance on European trade goods and higher prices offered for beaver pelts, beaver became an extremely prosperous commodity.[xvii] Ultimately, the end “result was the depletion of the [beaver] population, at least in some hinterlands.”[xviii] The beaver population throughout North America was decimated as the English, French and Indigenous people took advantage of the surge in pelt prices that occurred because of the competition that French traders introduced into the fur trade industry. Therefore, it is unprincipled to solely hold Indigenous people responsible for the environmental degradation caused by the fur trade because increased reliance on trade goods forced Indigenous trappers to obtain more pelts in order to continue to thrive, and all three parties participated in the industry. Competition between the English and French decimated the beaver population throughout North America as all three parties took advantage of the surge in fur prices. Therefore, it is unfair to blame only Indigenous people for the environment degradation.

In addition to the environmental degradation that occurred as beavers were over-harvested to near extinction, the plains bison population in Southern regions of North America was also drastically affected by unsustainable hunting practices as a result of technological advances in hide tanning. Scott Taylor stated that “10 to 15 million [bison] were killed in a punctuated slaughter in a little over ten years” as a result of a drastic increase in demand for bison leather.[xix] Before the 1870s, tanning bison hide was a laborious process that “required ingredients from the buffalo themselves,” but European tanners developed an easy and cost-effective way to tan plains bison hide which led to a bison hide boom in North America.[xx] The growing popularity of buffalo hides coincided with the industrial revolution as hides were used as industrial belting for machinery throughout Europe.[xxi] Similar to beaver, the growing demand for buffalo hides resulted in a drastic increase in hide prices. As a result, both European hunters and Indigenous people exploited this resource.[xxii] Thus, the over exploitation of animal populations was not restricted to one species. Additionally, Indigenous people, again, were not solely responsible for the depletion of the plains bison population because they were hunted mainly for industrial applications throughout Europe, and European hunters also participated in the hunting campaigns.

Environmental degradation also occurred as Indigenous people throughout North America became increasingly reliant on European trade goods and supplying furs for trade became an integral aspect of Indigenous survival. According to Carlos and Lewis, Indigenous people began to rely on European goods including knives, kettles, blankets and other items used for food production or hunting because they were a vast improvement to traditionally made stone or bone tools.[xxiii] Moreover, these tools “played little part in the harvesting and preparing of beaver pelts.”[xxiv] Thus, Indigenous people became severely reliant on European goods for their basic survival needs. As Indigenous people transitioned from tools made from traditional materials to European manufactured tools, harvesting animal furs became a venture to gain as much profit as possible through the trading of furs than for resources such as meat, bone and furs for clothing. Additionally, “the total time spent in the fur trade … increased” because purchasing their supplies allowed Indigenous people to spend less time acquiring producer goods.[xxv] As a result, beaver, bison, and other fur bearing animals were hunted in greater numbers despite their dwindling populations. Therefore, the shift in Indigenous consumerism habits further depleted fur bearing animal populations as Indigenous people began purchasing their tools instead of assembling them from natural materials.

Indigenous consumerism habits changed again as they were subjected to greater European influence and this further degraded the ecological balance of the environment in North America. In the early 1770s, producer and household good purchases declined from sixty percent to around thirty percent as Indigenous people began purchasing increasing amounts of luxury goods such as alcohol, tobacco, beads and jewelry.[xxvi] Carlos and Lewis explained that Indigenous people “responded to the new [trade] options in much the same manner as colonials and many Europeans of the time.”[xxvii] It is well known that Europeans used to accumulate material wealth and dress according to their social status. Once in North America, European traders attempted to instill their values regarding accumulation and status on Indigenous people. Initially, Indigenous people remained unimpeded by European influences regarding consumerism, but overtime, they also began to value luxury goods that displayed their social status. The change in consumerism habits contributed to the copious number of animals that were harvested for their furs. Thus, the extent of environmental degradation in North America was closely connected with consumerism habits of both European and Indigenous people because a greater number of furs were required to meet changing consumerism trends.

The absence of a legal system that successfully impeded encroaching on another person’s land for hunting purposes also contributed to environmental degradation in North America because trespassing hunters were not held accountable for over-harvesting beaver and other fur bearing animal species. McManus stated that many Indigenous nations in present day Quebec and Labrador had established hunting territories that were reserved for individual families and isolated from other band members.[xxviii] The author further explained that the “pattern of life for the Indian families in these tribes was seasonal” because they spent the winter months hunting beaver, deer, moose and caribou on their individual hunting territories before migrating to join the rest of the band in the summer.[xxix] This system encouraged families to practice sustainable harvesting techniques as they were responsible for maintaining animal populations for future generations and the seasonal migrations allowed animal populations to recover throughout the summer months, but this system began to be abused as the fur trade industry became progressively profitable. According to McManus both Indigenous and European hunters were caught trespassing in these exclusive hunting territories, but “no social machinery existed … for the enforcement of hunting rights.”[xxx] Moreover, the absence of a social system to deal with trespassers meant that “the costs of enforcement would have had to be borne by the individual” families.[xxxi] This meant that trespassers often escaped punishment for encroaching on exclusive hunting territories because families did not have the resources to adequately deter lawbreakers from intruding on their territories.

Trespassers could also escape prosecution through the exploitation of loop holes in Indigenous laws. According to Indigenous law “individuals could not withhold goods from other members of the band who were ‘in need.’”[xxxii] Therefore, “the individual had the granted right to satisfy his hunger and sustain his life.”[xxxiii] This meant that if a member of an Indigenous nation was destitute, they had the legal right to hunt in exclusive hunting territories in order to sustain themselves.[xxxiv] As the fur trade became more prominent in the lives of Indigenous people some people began to abuse this legal right and claimed to be starving in order to exploit resources from hunting territories owned by other community members. Additionally, these legal trespassers were less inclined to consider the ecological damage that they were causing because they did not own the land that was being degraded. As a result, the beaver population in these regions was depleted to near extinction as people continued to over-harvest these animals under the guise of starvation.

Re-evaluating our understanding of historic events has been an integral part of the truth and reconciliation process as Eurocentric prejudices towards Indigenous people have either vilified them, or left them out of history completely. Through increased education about Indigenous culture and history, it can be determined that Indigenous people are not the only party that should be under scrutiny for their role in the fur trade. As the fur trade grew into an increasingly profitable enterprise throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, French, English and Indigenous people capitalized on this industry. Additionally, there were many factors that contributed to environmental degradation throughout North America including an inadequate legal system to deter trespassers from hunting in exclusive hunting territories, an increased reliance on luxury items and superior production goods from European traders as well as a substantial inflation in pelt prices as a result of competition between French and English traders. Therefore, ecological degradation that occurred during the fur trade was a multifarious issue in which Indigenous people and Europeans were responsible.

Bibliography

Carlos, Ann M., and Frank D. Lewis. “Indians, the Beaver, and the Bay: The Economics of Depletion in the Lands of the Hudson’s Bay Company, 1700-1763.” The Journal of Economic History 53, no. 3 (1993): 465–494. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2122402?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents.

Carlos, Ann M, and Frank D Lewis. “Trade, Consumption, and the Native Economy: Lessons from York Factory, Hudson Bay.” The Journal of Economic History 61, no. 4 (2001): 1037–1064. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2697916?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents.

Government of Canada; Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada. “Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada.” Government of Canada; Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada, June 11, 2021. https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1450124405592/1529106060525.

McManus, John C. “An Economic Analysis of Indian Behavior in the North American Fur Trade.” The Journal of Economic History 32, no. 1 (1972): 36–53. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2117176?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents.

Ray, Arthur J. “Competition and Conservation in the Early Subarctic Fur Trade.” Ethnohistory 25, no. 4 (1978): 347–57. https://eds.s.ebscohost.com/eds/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=2&sid=215bd8eb-9c38-4e45-97c8-e306ecc9faba%40redis.

Taylor, Scott. “Buffalo Hunt: International Trade and the Virtual Extinction of the North American Bison.” The American Economic Review 101, no. 7 (2011): 3162–95. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41408734?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to Action. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission, 2015. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/british-columbians-our-governments/indigenous-people/aboriginal-peoples-documents/calls_to_action_english2.pdf.

[i] Government of Canada; Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada, “Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada,” Government of Canada; Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada, June 11, 2021, https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1450124405592/1529106060525.

[ii] Government of Canada; Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada.

[iii] Truth and Reconciliation Commission, Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to Action (The Truth and Reconciliation Commission, 2015), 7; Truth and Reconciliation Commission, 9.

[iv] Arthur J Ray, “Competition and Conservation in the Early Subarctic Fur Trade,” Ethnohistory 25, no. 4 (1978): pp. 347-357, 348.

[v] Ray, 349.

[vi] Ray, 349.

[vii] Ray, 349.

[viii] Ray, 349.

[ix] Ray, 348.

[x] Ray, 348.

[xi] Ray, 348.

[xii] Ann M. Carlos and Frank D. Lewis, “Indians, the Beaver, and the Bay: The Economics of Depletion in the Lands of the Hudson’s Bay Company, 1700-1763,” The Journal of Economic History 53, no. 3 (1993): pp. 465-494, 466.

[xiii] Carlos and Lewis, 470.

[xiv] Carlos and Lewis, 470.

[xv] Carlos and Lewis, 470.

[xvi] Carlos and Lewis, 466.

[xvii] John C McManus, “An Economic Analysis of Indian Behavior in the North American Fur Trade,” The Journal of Economic History 32, no. 1 (1972): pp. 36-53, 45.

[xviii] Ann M. Carlos and Frank D. Lewis, “Trade, Consumption, and the Native Economy: Lessons from York Factory, Hudson Bay,” The Journal of Economic History 61, no. 4 (2001): pp. 1037-1064, 1061.

[xix] Scott Taylor, “Buffalo Hunt: International Trade and the Virtual Extinction of the North American Bison,” The American Economic Review 101, no. 7 (2011): pp. 3162-3195, 3163.

[xx] Taylor, 3168.

[xxi] Taylor, 3169.

[xxii] Taylor, 3190.

[xxiii] Carlos and Lewis, 1049.

[xxiv] Carlos and Lewis, 1049.

[xxv] Carlos and Lewis, 1060.

[xxvi] Carlos and Lewis, 1049.

[xxvii] Carlos and Lewis, 1061.

[xxviii] McManus, 41.

[xxix] McManus, 41.

[xxx] McManus, 43.

[xxxi] McManus, 43.

[xxxii] McManus, 50.

[xxxiii] McManus, 50.

[xxxiv] McManus, 50.

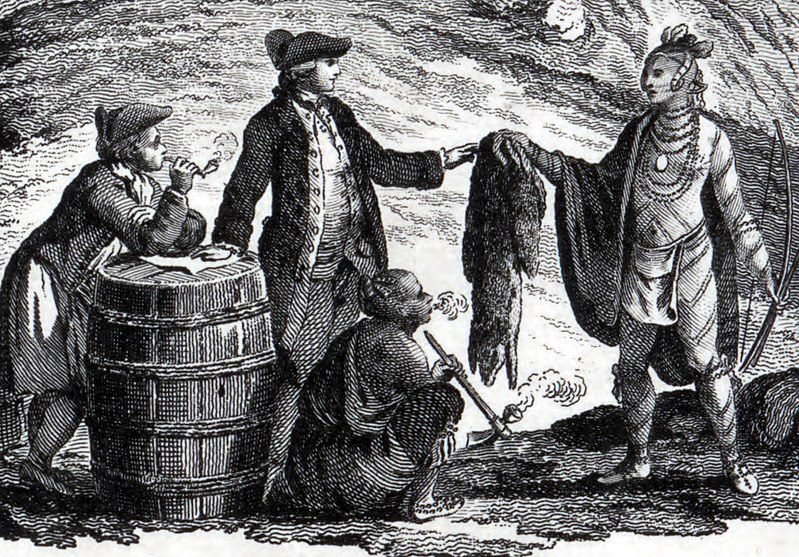

Library and Archives Canada – originally from: Cartouche from William Faden, “A map of the Inhabited Part of Canada from the French Surveys; with the Frontiers of New York and New England”, 1777

Author’s Bio: Kelly Laybolt is currently enrolled in his fourth year of the Bachelor of Arts Program at the University College of the North (UCN). Recently, he served a one-year term as a student representative for the UCN Thompson campus on the Learning Council Committee as well as the Executive Learning Council Committee. Through UCN, Kelly has had the opportunity to learn extensively about Indigenous history and culture. This education has provided him with a greater understanding of the Truth and Reconciliation process and why it is integral to dispel Eurocentric notions in order to work towards a post-colonial future. Upon the completion of his Bachelor of Arts degree, Kelly hopes to enter the Education program. After university, he hopes to teach at the elementary school level and use the knowledge he has acquired about truth and reconciliation to further work towards post-colonialism..

Instructor’s Remarks: Kelly Laybolt’s research paper for the course of “History of the Fur Trade and Aboriginal Societies” investigates the environmental impacts of the fur trade in the lands that would eventually become Canada. It is a carefully crafted and nuanced examination of a complex interplay of the various forces involved. Using important scholarship, Laybolt was able to develop a compelling argument that situates Indigenous ways of knowing and living with those of the European traders with whom they interacted. This paper helps us to understand and acknowledge the intricate bonds of connection between the various groups and communities and is an important contribution toward environmental history. It also peels away old assumptions and accumulated layers of Eurocentric concepts that have too long dominated our understandings of our complex past. This work and others like it help to address and correct many of these problems outlined by Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation process. The past has always been a complex and difficult place to inhabit and investigating it is a delicate exercise in attempting to sort out the scant records and traditions that remain to develop an ever-evolving move to truth and understanding. Laybolt had done an admirable job in getting us toward this goal. (Dr. Greg Stott)